Grief is not an illness or disorder. Grief is a normal reaction to loss, and because loss in its various forms is part of the human experience, grief is universal. Grief is also a process— albeit a non-linear one. This means that grief requires adjusting to the new normal of life in the aftermath of loss— and, that grief doesn’t have to belong to your new normal forever. Many people are able to move through their tunnel of grief and safely and successfully emerge out on the other side. (Some people need the help of bereavement and/or mental health professionals to do this.)

Grief also hurts. When someone you love dies, or when an important relationship ends, that experience signifies the loss of a person you cannot replace, the joy and comfort of their presence, and the bonds of connection you once shared. In the aftermath of their loss—and sometimes in the lead-up to their loss—painful thoughts, emotions, and physical symptoms can arise. These can come and go, and they can vary in intensity depending on your individual circumstances, such as whether you may have an underlying mental health condition like anxiety or depression.

While grief is a universal human experience, then, individuals can grieve in different ways (some of them healthy, and some of them not). There are multiple healthy ways to grieve, too, so that one person may cope with and process their grief very differently from how another person attends to the same process.

Statistics on Grief

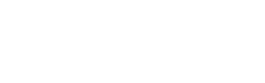

Grief and grief-related medical complications are common among adults. One psychiatric study in the March 1998 issue of the British Medical Journal found that 55 out of 200 visits to general practitioners—roughly one in four visits—were related to some type of loss. The same study noted that:

- “After a major loss, such as the death of a spouse or child, up to a third of the people most directly affected will suffer detrimental effects on their physical or mental health, or both.”

- Bereaved loved ones are at greater risk of death from heart disease and suicide, and the onset or relapse of a variety of “psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders.”

- 31 percent of 71 elderly psychiatric patients had recently been bereaved, according to another study.

Children are also not immune to grief and its health impact. Statistics from Children’s Grief Awareness Day reveal that one in five children will experience the death of someone close to them by the age of 18, and that bereaved children experience a wide variety of emotional and behavioral symptoms.

While typical estimates suggest that the average mourning period after a loss lasts between six months and one year, individuals who lose a spouse may require as long as five to eight years to fully adjust to the loss, according to findings reported in the Journal of Happiness. Still harder to recover from: the death of a child.

What Is Grief? How Experts Define It

Experts on grief have given the following definition based on research: that grief is a series of “emotional, cognitive, functional and behavioral responses” to death or other kinds of loss such as “loss of youth, of opportunities, and functional abilities.” The same research findings have emphasized that:

- grief is a “process,” not a “state,” meaning that bereaved people move tend to move through various stages of grief.

- grief can vary in its nature and severity between people— a fact that has led to the classification of quite a few different types of grief.

- the two major ways in which grief has been classified are as “normal” or “uncomplicated” grief and “complicated and/or prolonged” grief.

- complicated and/or prolonged grief can co-occur with major depression, a life-threatening mental health condition that can be characterized by thinking of or attempting suicide.

People who study grief and help others to move through it tend to agree that there’s, broadly speaking, a kind of movement to grief that looks as follows:

- The initial shock or denial in the immediate aftermath of the loss (especially if the loss was sudden and unexpected)

- An ensuing period of acute grief characterized by intense emotional pain

- A period of accepting the new normal and adjusting to life in the midst of the loss— or, a more prolonged period of getting stuck in the acute phase

Uncomplicated vs. Complicated Grief – Symptoms of Grief

The consensus of research into what constitutes “normal” or “uncomplicated” grief is that it consists of these components:

- Numbness and disbelief.

- Anxiety from the distress of separation.

- A process of mourning often accompanied by symptoms of depression.

- Eventual recovery.

But, the same research, published in April 2017, in “Grief, Bereavement and Coping with Loss,” a training manual for health professionals, has noted that, “Grief reactions can also be viewed as abnormal, traumatic, pathologic, or complicated,” stating that “diagnostic criteria for complicated grief have been proposed” as a way to identify complicated grief, sometimes called “prolonged grief disorder.” These criteria—which only a bereavement or mental health professional is qualified to assess in an in-person consultation—include the following:

- Criterion A: A person has experienced the death of a significant other, and their response involves three of the four following symptoms, experienced at least daily or to a marked degree:

- Intrusive thoughts about the deceased.

- Yearning for the deceased.

- Searching for the deceased.

- Excessive loneliness since the death.

- Criterion B: In response to the death, four of the eight following symptoms are experienced at least daily or to a marked degree:

- Purposelessness or feelings of futility about the future.

- Subjective sense of numbness, detachment, or absence of emotional responsiveness.

- Difficulty acknowledging the death (e.g., disbelief).

- Feeling that life is empty or meaningless.

- Feeling that part of oneself has died.

- Shattered worldview (e.g., lost sense of security, trust, control).

- Assumption of symptoms or harmful behaviors of, or related to, the deceased person.

- Excessive irritability, bitterness, or anger related to the death.

- Criterion C: The disturbance (symptoms listed) must endure for at least six months.

- Criterion D: The disturbance causes clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Complicated grief reportedly affects as many as 10 percent of the population, according to a June 2009 study in World Psychiatry— so is not uncommon. A bereavement counselor will be able to evaluate the above criteria to determine whether you are experiencing normal grief symptoms or complicated grief symptoms. In the first stages of grief, it is not abnormal to experience intense feelings and extreme reactions. But when these feelings continue over a prolonged period, they may require mental health intervention and treatment.

Both normal and complicated grief can therefore be characterized by physical and emotional symptoms.

Physical symptoms of grief can include:

- Dizziness or shortness of breath

- Tightness in the chest

- Extreme restlessness

- Severe butterflies or painful sensations in the gut

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Sleep problems

- Physical weakness

- Digestive problems

- Changes in appetite

- Frequent bouts of illness

- Muscle tension or soreness

Emotional symptoms of grief can include:

- Emotional numbness or detachment

- Guilt

- Anger

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Sadness

- Loneliness

Types of Grief and Grief Reactions

With progress in efforts to understand grief and its impact on individuals, clinicians and bereavement specialists are now able to classify grief according to different “types.” For one thing, they’ve found that even normal grief has different classifications. Second, in addition to normal and complicated grief, they have discovered and named other types of grief and grief reactions. All of them are as follows:

- Normal Grief spans a broad range of reactions to loss, from the more demonstrative and expressive to the more closed and reserved, depending on individual personalities and practical needs. Some people may not let themselves grieve until their duties have been attended to relating to the loss of their loved one (such as planning for the funeral, caring for their loved one before they die, etc). Other people may not want to open up about their feelings out of fear that they won’t be able to handle their daily duties. What this means is that even normal grief can fall into different categories:

- Inhibited Grief – when a person may appear to be largely unaffected by the loss, going about their daily tasks, but may become sick or experience physical symptoms

- Masked Grief – when the bereaved suppresses their emotional symptoms of grief, or intellectualizes their grief without dealing with the underlying emotions, so that their grief expresses itself in physical symptoms

- Delayed Grief – when symptoms of grief kick in at a much later time than is typical

- Complicated Grief, or prolonged grief characterized by long-lasting and severe emotional reactions, is reportedly twice as common among those grieving the loss of a loved one to suicide. Like suicide, other acute or traumatic forms of loss of a loved one can be associated with complicated grief. One example: the “ambiguous loss” of a loved one to dementia.

- Chronic Grief, not unlike complicated grief, can arise in cases where a loved one dies from a violent or traumatic act. The main difference is that chronic grief can last for years. This type of grief, like complicated grief, can cause major depression and/or other mental health problems. The good news is that with trusted mental health treatment, you can recover from major depression and go on, through various measures, to come out on the other side of chronic grief.

- Anticipatory Mourning can happen before the loss occurs, and is common in situations when a loved one is dying from a terminal illness and has a limited amount of time to live. In these situations, end-of-life conversations, and issues like unfinished business, bucket list to do’s, and how a loved one would like to be remembered at their memorial service, can cause grief to set in earlier, as a function of participating in the more drawn-out loss of a loved one.

- Secondary Loss can occur when the bereaved person experiences additional losses—of income, security, social support, quality of life, etc.—incurred as the result of a loved one’s death. If the loved one who died was the main breadwinner in the family, for example, their loss may mean that the bereaved spouse must now get a job or vacate the family home. Sometimes a role or sense of identity may be the secondary loss that someone grieves.

- Absent Grief describes when a person is in total denial about their loss, not able to admit they have experienced a loss. Even if they are able to acknowledge what has happened intellectually, they behave as if nothing has changed.

- Cumulative Grief can result from an experience of multiple losses in a short period. Those who find themselves simultaneously grieving multiple losses at the same time can experience a delayed or absent grief reaction; or, after one loss in a series of losses, they may experience feelings and symptoms of grief over a much earlier loss.

- Disenfranchised Grief can occur when society at large does not recognize or acknowledge the loss: the loss of someone you have loved in an illicit relationship, for example; or, a miscarriage. The experience of gay men who lost their partners to AIDS during the high point of that epidemic in the 1980’s might be another example.

Causes of Grief

The death of a loved one, while a leading cause of grief, is by no means the only reason people grieve. There are many forms of loss in this life. These can range from the loss of a pet to the loss of marriage to the loss of a job or one’s independence as part of the natural aging process. The diagnosis of a chronic illness can be another source of grieving. Many of these more garden-variety losses can trigger grief, whether normal or complicated.

Less common causes of grief, and factors that correlate with a higher risk of complicated grief can include:

- exposure to acute stress and/or a traumatic event, such as a near-death experience and/or the loss of one’s home to a natural disaster

- an experience of violence and/or a violent loss, such as injuries in combat and/or witnessing war casualties

- a series of recent losses

- and/or an underlying mental health condition.