Kim Koger doesn’t remember much from her early years in a foster home in South Korea — and the circumstances that brought her there are still hazy. Her birth parents had reportedly abandoned her at a police telephone booth. There was no birth certificate.

Those first childhood memories are hard to access and faint at best. Sometimes Kim wonders if they’re even real or just a figment of her dreams: the foster home on a hill and its three buildings, each with a distinct function (sleeping, eating, and praying); the stomach aches and malnourishment; the day when someone came to the door asking for money and was turned away.

Growing Up and Feeling Like an Outsider

Kim and her three siblings would each come to the United States at different times: Kim’s older brother first, then Kim, then her younger brother, then her older sister.

Kim and her three siblings would each come to the United States at different times: Kim’s older brother first, then Kim, then her younger brother, then her older sister.

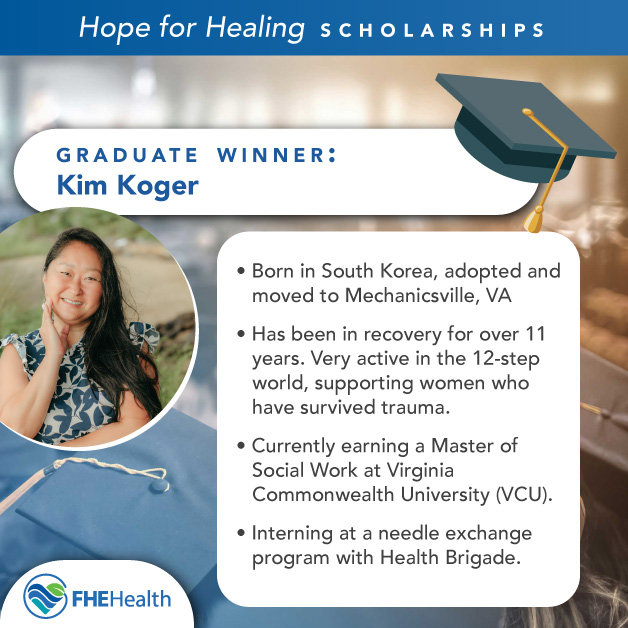

Kim was five when she settled in Mechanicsville, Virginia, just outside of Richmond, after being adopted by a Caucasian couple through the group Catholic Charities.

Mechanicsville was a mostly white, conservative, suburban community. As one of only three Asian students at school, Kim remembers “feeling very different from everyone else” and always wanting to fit in. It didn’t help that when she became a U.S. citizen, her second-grade class turned the occasion into “a huge history lesson.”

When the Substance Use Began

Kim was in her mid 20s when the substance use began. She had transferred to Virginia Commonwealth University from Virginia Tech and was preparing to become an art teacher while waiting on tables on the side. But she was struggling to keep up with the demands of her work and studies. The substance use began as “a recreational thing, and once it started, it very quickly took me down,” she said.

Looking back at that period, Kim points to a few triggers. The biggest one was the death of her younger brother, who took his own life. Substances provided “an escape or release,” however temporary, from the pain and grief of that loss.

“Relationships and the desire to find unconditional love” were another trigger. “There was always a search for that,” Kim said.

Trauma, Survival, and Resources for Rebuilding

During the next roughly 10 years of active addiction, Kim became intimately familiar with what it’s like to “lose everything more than once” and narrowly survive unspeakable things:

Your spirit just gets broken. I remember being very angry at God, because I had no idea that this dark side of life existed. I grew up somewhat sheltered, so to see such darkness was incredibly jilting and scary. And when I’d come to, the reality of what I’d seen would take me right back into using substances.

Yet Kim didn’t just survive all the cumulative trauma and loss — she managed to come back from it and chart a healthier and more hopeful course. What’s striking is that after hitting rock bottom so many times, she went on to rebuild her life. What inner and outer resources did that feat demand? we wondered.

God’s Protection and Help

Kim mentioned a few, starting with God’s protection and help:

I think God was looking out for me and keeping me safe. There were so many experiences that I encountered where I should not even be alive. I hit 5,000 bottoms, but … it took every last door being shut on me for me to come to myself and say, “I’m truly done.”

People Who Planted Seeds of Hope

Certain people also “planted seeds” that became a source of hope and healing. One of those people was Kim’s probation officer. Then there was the woman who paid for Kim’s bed fees at a sober living home. Kim had stayed there briefly before relapsing. This woman’s love and her dedication to 12-step recovery made a lasting impression, “so when I finally was ready [for long-term recovery], I called her,” Kim said. This woman would later become Kim’s sponsor in AA, mentoring Kim for eight-and-a-half years.

The Pain, Shame, and Hopelessness

At a certain point, Kim reached her own threshold for tolerating the pain and consequences of active addiction. She ultimately couldn’t run away from “the feelings of utter hopelessness and feeling so alone in [addiction] … and my own shame and guilt of how I ended up there.” This reckoning with reality became another motivation to finally wholeheartedly embrace recovery.

Life in Recovery: What It’s Like

Kim’s life today looks very different than it once did. The 45-year-old single mother has been in long-term recovery since September 11, 2013 (“my sobriety date,” as she put it in her essay). She’s also very active in the 12-step world. She has taken recovery meetings to detox centers, treatment facilities, and multiple correctional institutions, and has served in various service and leadership roles.

Kim’s life today looks very different than it once did. The 45-year-old single mother has been in long-term recovery since September 11, 2013 (“my sobriety date,” as she put it in her essay). She’s also very active in the 12-step world. She has taken recovery meetings to detox centers, treatment facilities, and multiple correctional institutions, and has served in various service and leadership roles.

When asked what life in recovery is like, Kim described it as “this amazing built-in community … where else do you go in life where you share all your darkest moments? And, in the midst of it is showing up and accepting love.”

The most rewarding aspect of 12-step recovery has been sponsoring other women who, like Kim, have survived trauma:

Sponsoring others who have survived trauma, working one-on-one, sharing our experiences, releasing the trauma, and walking through the steps and whatever it is they’re going through has been the most powerful experience.

As fulfilling as her life in recovery has been, it has not been without its challenges, as Kim was careful to point out:

People often think that everything’s going to get better when recovery begins, but really that’s when the real work starts. When I came in this last time, I did all the things that you’re supposed to do — to an extensive degree. The reality is that people in recovery struggle a lot … I struggled a lot with my identity, how to be in relationships, and how to not allow the world to dictate who I was, because there was a lot of people pleasing.

Life shows up, and there’s illness, break-ups, disappointments, and financial stress. Recovery is about learning how to live with life as it is, with all the beauty, stresses, and insecurities, and learning how to grow and deal with my emotions — the feelings of rejection, abandonment, anxiety, and disappointment — so I don’t go back out and use substances again.

Graduate Studies and Research and Fieldwork

Kim was taking a class toward certification as a Peer Recovery Specialist when she got the idea to apply — today, she’s earning a Master of Social Work at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU).

Kim is also interning in a needle exchange program with the organization Health Brigade and gaining new insights in harm reduction policies; through involvement in two recovery scholars’ groups, she is also learning about how to make recovery services more accessible to people of color. And, as part of a five-year study funded by the National Institute of Health and the National Institute of Drug Abuse, Kim is contributing her lived experience to improve the delivery of substance use and recovery services.

What is she learning in the process? “The value of lived experience” in conversations about addiction treatment reform, she said.

“Bridging the Gap”: Professional Aspirations

After graduate school, Kim plans “to bridge the gap between clinical social work and grassroots recovery support”:

There’s a disconnection between case management and grassroots recovery. A lot of peer-run organizations such as recovery community organizations (RCOs) offer a certain kind of support, but what’s often missing are the significant social work services, which help the individual heal from that internal trauma. If we’re facing a lifetime’s worth of trauma and unresolved issues that led us to addiction, then it’s going to take a great amount of time and services to help people heal. The “gap” is that it’s rare to see a holistic, comprehensive program that’s long enough to address all those needs.

The Power of “Feeling Seen, Heard and Supported”

Kim began her essay with these words: “More than anything, I want to help people feel seen, heard, and supported as they navigate their healing journeys.” What would she say to anyone who feels unseen, unheard, or helpless in dealing with a mental health or substance use disorder? Kim shared what helped her when she was in that space:

Kim began her essay with these words: “More than anything, I want to help people feel seen, heard, and supported as they navigate their healing journeys.” What would she say to anyone who feels unseen, unheard, or helpless in dealing with a mental health or substance use disorder? Kim shared what helped her when she was in that space:

- “Asking for help and support”

- Finding mentors/role models — “Paying attention to the people who are exemplifying what you want for yourself … People will tell you things in recovery but pay attention to what they do.”

- “Being open to when it’s time to change”

- “Being patient and seeking out new tools in that period of discomfort”

For Kim, this work of healing and recovery is a spiritual journey, one that’s both very hard and incredibly rewarding: “When you’re on the spiritual path, it continues to get narrower and narrower. But the pay-off and the freedom — if we can stay in that place, I see glimpses of immense freedom.”