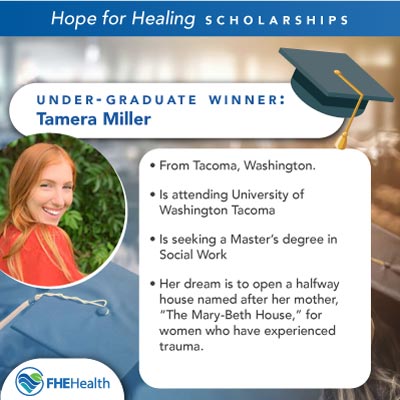

Each year FHE Health awards two outstanding individuals with a $5000 scholarship to help further their education in the field of addiction, mental/behavioral health and/or psychiatry. In this second spotlight blog, you’ll meet Tamera Miller. She is the undergraduate recipient of the 2021 Hope for Healing Scholarship. Catch her moving story, much of it in her own words, below.

Tamera Miller likes to use the metaphor of a butterfly in its chrysalis to describe the main theme of her life story:

“I was a young girl when I learned never to help a butterfly out of its chrysalis. The only way butterflies can strengthen their muscles to fly is by beating them against the hard encasing until it opens. If you help the butterfly, you prevent it from developing the muscles it needs to survive … At 30 years old, I know that I am like this butterfly. I had to face many struggles in my life, some of which felt too immense to overcome. I now see how these challenges made me into the person that I am today. They made me resilient and strong, and they allowed me to develop my ability to fly.”

The Impact of Addiction and Mental Illness at a Young Age

Parental alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness were the backdrop for Miller’s formative years. With her dad often away and her mother, “a drug addict with severe mental illness,” often “incoherent,” “no one came home to see if my homework was finished or ask me why I failed every grade in K-8,” Miller wrote in her personal essay.

Parental alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness were the backdrop for Miller’s formative years. With her dad often away and her mother, “a drug addict with severe mental illness,” often “incoherent,” “no one came home to see if my homework was finished or ask me why I failed every grade in K-8,” Miller wrote in her personal essay.

Miller’s late mom Mary Beth is the inspiration for Miller’s dream to eventually found a halfway house for women like her mother. When asked to share more about her mother, Miller began her recollections at the age of eight. It was a pivotal year:

“Before I was eight, my mother was somewhat normal. She had beautiful permed blonde hair, worked at a law office and always had her acrylics freshly painted. I say ‘somewhat normal;’ there were things about her that were off. Like we could not keep wooden spoons in the house, and the sight of one sent her into a panic.

When I was eight, my mom got kidney stones and was given pain pills. It wasn’t long until my mom had become hooked on pain pills and methadone. For 10 years, I watched as my mom turned into the shell of the human she used to be. She lost everything. My stepdad left her. She lived in a halfway home; her hair had become thin and flat; her skin was gray, and her nails looked as if she had been digging outside for weeks.

One time I was walking with her down the street, and a police officer stopped her because I was young, and she looked like a homeless person. She died shortly after that in a halfway home.

My mother had been diagnosed with OCD, and another therapist once told me that my mom had Munchausen’s by proxy, because one night she told my friends’ moms that I had a spine disease and was going to be confined to a wheelchair for most of my life.”

(Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is a mental health problem in which a parent or caregiver makes up or even causes an illness or injury to a person in their care.) Miller said she cried for hours to her dad after hearing that she would end up in a wheelchair. For Miller, the incident also signified that her mother had “lost touch with reality. We could never get her back.”

The Cycle of Generational Trauma in Her Family History

Much later on—when Miller was an adult and coming to terms with her relationship with her late mother—Miller began to better understand why her mom struggled with addiction and mental illness:

“I found my mother’s biological sister on Ancestry.com a few years ago. She had been looking for my brother and me, too. She told me my mother had a very traumatic past and mentioned the wooden spoons. She said she endured more trauma than any kid should ever have to. She said that their mother had suffered from alcoholism.

When my mom and her sister were adopted by another family, my mom was handed over with the front of her shoes cut off because her feet could no longer fit in them; and she had been wearing the same clothes for weeks.

My mom had been to dozens of institutions and rehabs … She could never stay sober long enough to figure out what was going on. She would get a few days, and then we would lose her again.”

What It’s Like Growing Up with Adversity

When Miller was studying psychology later in life as an adult, a professor encouraged her to focus her research on the long-term effects of childhood adversity. Of course, the subject hit close to home. If anyone knew about what it’s like to grow up with adversity, it would be Miller. What was it like? For starters, it was like living in a “small cardboard box”:

“I was living with my mom, stepdad and three stepbrothers in a two-bedroom apartment. My mom had made me a tiny home in the living room made out of a box with a cutout door and a window. When I was growing up, I was so mad at her for making me that box as a room, but now I know that she was giving me all that she could as a kid, and that box was more comfortable than sleeping in a room with three adolescent boys.”

It was not uncommon for Miller to come home and find Mom “passed out in the room when I would get home.” There were also the times when:

“I came home to a homeless man in her kitchen once, and I made the mistake of waking her one time only to get a punch in the gut. She didn’t know it was me, or I don’t think she would have done it. She was not in her right mind.”

Eventually, Miller ended up living with her dad, who would have sole custody.

Drug Use and Addiction in the Teen and Young Adult Years

“When I was 13, I turned to drugs as a coping mechanism,” Miller wrote in her personal essay. She started with crystal meth. By age 15 all of her hair had fallen out, and she was under 100 pounds. That is when….

“My body gave out, and I had my first overdose. I was supposed to come out of the hospital either dead or mentally handicapped. I woke up a few days later in a mental institution, and then a few days after that, I came to in rehab. I never graduated from that rehab program and could never acquire more than 30 days sober.

I was kicked out of high school, went to an expulsion school and continued drinking and doing drugs there. I was lucky enough to be in a school where we caught up on graduation credits by filling out education packets.

I managed to go to rehab and fill out enough simple education packets to give me the credits I needed to graduate from a continuation high school.”

The overdose was not a wake-up call: “I was 15 and full of resentment. At the time, I just wanted to get my weight back up so I could slip back off into oblivion.”

Getting Sober and Back into School

It took eight more years of “drinking, resentment and grief” to finally get sober and stay that way. At one point, when Miller was in recovery and had started her first semester at a community college, her mother died. She remembered the night that her mother passed away:

It took eight more years of “drinking, resentment and grief” to finally get sober and stay that way. At one point, when Miller was in recovery and had started her first semester at a community college, her mother died. She remembered the night that her mother passed away:

“My mom had broken out of her rehab to come to visit me on my prom night, and I told her I didn’t want to see her. I was so resentful at her that I was mean and cold to her in my teenage years. It was the day before my 18th birthday, and she called me from another rehab program to say, ‘Happy Birthday.’ I told her that I was not interested in talking to her. That night she passed away in her sleep. It took me years to forgive myself for that.”

The loss of her mother triggered another relapse and caused Miller to drop out of school.

At 25, Miller got sober, and this time recovery stuck. She began to prepare for another attempt at college and knew it would be tough. In fact, she had to ask a friend to teach her some basic grammar and arithmetic skills.

“I knew getting into college-level classes wouldn’t be an easy feat, but with persistence and determination, I refused to give up.”

At the same time that she was preparing for college, Miller was “digging my way out of childhood poverty”:

“I began working full-time to save a deposit for an apartment. I lived out of the back of my old Chevy Trailblazer and studied for my anatomy exams with a flashlight perched on a pile of clothes.”

Over time “little victories led to big victories.” Today Miller has five years of sobriety and a secure job that pays the bills. She will also be the first person in her family to graduate from college (the University of Washington Tacoma, where she will major in psychology).

Making a Difference in the Lives of People with Addiction and Mental Illness

Today Miller regularly shares her story at mental institutions, inpatient rehabs and women’s juvenile facilities:

“I am talking to the same 13-year-olds doing meth … I got to speak at the same rehab I went to when I was 15. I got to speak at the same mental institutions I was thrown into. They are shocked when they find out my teeth are fake, and that I have been in rehabs and institutions and have gone through the same struggles with my family.

Sometimes I will go in with a blazer on, and when it is time to relate to them, I take the blazer off, and I am covered in tattoos from my wrists to my spine. I regret getting my tattoos, but they tell a story of another time and help me remember who I was and who I have grown into today.”

What is the most important message that Miller wants to convey to her audience?

“The most important message I want them to hear is that as a survivor of childhood trauma and domestic abuse, I promise that your past does not have to be a script for your future, and it’s possible to release your old story and create a new one. Trauma does not have to define you. You are more than your trauma.”

Who Have Been the Biggest Positive Influences in Her Life and Recovery?

“I have a small-knit group of friends in AA who are my biggest cheerleaders and my soulmates,” Miller said. “My sponsor, who I swear saved my life, and I still call her every day even five years sober—she will celebrate 40 years sober this year.”

Miller also has a serious boyfriend who is a “huge supporter of me and wants to contribute to the foundation I want to open when I am done with school.”

Another one of her biggest supporters: “my big brother.” The two siblings had no relationship until Miller got sober. “Today he is one of my best friends, and I call him about everything. He could not be more proud to see where I have come.”

How Therapy Helped with Panic Attacks in Recovery

Recovery did not suddenly make everything easy. One year after she got sober, Miller began to experience panic attacks and had to seek help:

Recovery did not suddenly make everything easy. One year after she got sober, Miller began to experience panic attacks and had to seek help:

“That was my introduction to psychotherapy. I think that I drank away my childhood and teen years for so long that all those feelings rose back up to the surface and came out in panic attacks when I got sober.

I realized that growing up through trauma is a bit like going on a cross-country trip. Along the way, you pick up fast food and drinks at gas stations and accumulate more and more trash in the back of the car. When you stop drinking and numbing the past, it can be like braking really fast and watching as all of that garbage from the back comes hurtling forward. You’re left with that mess right in front of you to clean up.

Today I continue psychotherapy once a week, years later, the same way I continue to be active in a 12-step program for alcoholism and addiction. These things will always be a part of my life so I can continue to help others.”

Most Important Contributions in the Field?

What does Miller hope will be her most important contributions to the mental and behavioral health field?

“I want a program for women to find a safe place to heal,” Miller said. (She was referring to the foundation and halfway house that she hopes to one day found and name after her late mother Mary Beth.) Miller went on to share more of that vision:

“[The halfway house] will be a place where women can attend parental classes, find AA meetings and access health screenings for themselves and their children (including the ACE score test), psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, a warm meal, childcare and a job … I want it to feel like you’re walking into a home … like a new story. I want it to be everything that my mom would have wanted and needed as a parent and a child. I want it to bring families back together. I want it to end generational cycles of trauma.”

Miller added, referencing her own experience, “I want it to be the reason a young girl doesn’t have to sit on a beach and read her amends letter to her mom, who passed away. That is what I want to contribute to this life through the Mary-Beth Foundation.”