Nearly all fentanyl sold on the streets of America enters the country through international mail. In early 2018, a Senate investigation discovered the government simply was not prepared to stop the influx of fentanyl from China. The report, which scrutinized six online fentanyl sellers, found that five operated in China; the location of one seller could not be established. These particular vendors mailed hundreds of packages of fentanyl to over 300 people in the U.S., relying on the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to send millions of dollars’ worth of fentanyl overseas.

How do Chinese fentanyl sellers get away with this? Lawmakers say it is the flawed, outdated tracking systems used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (USCBP) and the USPS that allow packages of fentanyl to evade detection.

In 2016, nearly 65,000 Americans died from overdosing on opioids like fentanyl. The federal government declared the opioid epidemic a national emergency in the fall of 2017. Declaring a national emergency to fight the opioid epidemic frees up extra money to be provided to state and local communities for drug rehab, prevention measures and helping those at risk for opioid addiction.

Florida’s Fentanyl Problem

Opioid overdose rates in Florida have doubled in the past five years. In addition to China failing to enforce laws regarding the production and sale of fentanyl, the increasing sophistication of the “dark web” has allowed Chinese drug dealers to mail an endless supply of fentanyl to Florida drug dealers.

Opioid overdose rates in Florida have doubled in the past five years. In addition to China failing to enforce laws regarding the production and sale of fentanyl, the increasing sophistication of the “dark web” has allowed Chinese drug dealers to mail an endless supply of fentanyl to Florida drug dealers.

The dark web is a subset of the Web where sites sell counterfeit money, hacking software, child porn, and drugs. To access the dark web, Chinese fentanyl sellers are using a virtual private network to avoid government detection and the TOR browser/network. Fentanyl mailed from China is usually marked as a prescription or herbal medication. In some cases, the drug is mixed with heroin or cocaine.

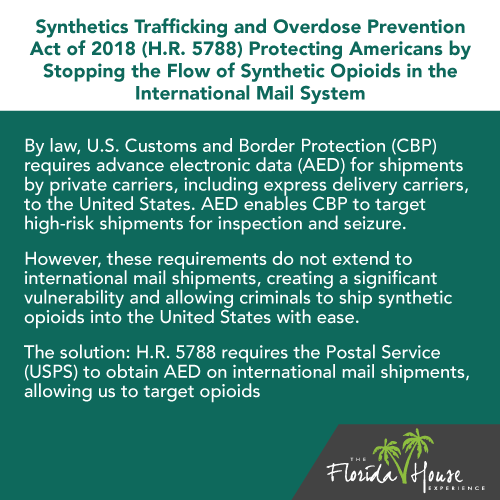

To assist Florida and other states suffering high rates of opioid overdoses, the Synthetics Trafficking and Overdose Prevention Act of 2018 (H.R. 5788) lists numerous laws soon to take effect for the purpose of stopping fentanyl from coming into the U.S. For example, this act will require the USPS to transmit advanced electronic data (AED) to USCBP on 70 percent of all international mail entering the U.S.; by 2020, that number rises to 100 percent. In addition, the bill directs the U.S. State Department to improve postal agreements with China and other countries suspected of mailing opioids to the U.S.

Why Fentanyl Is So Deadly and Addictive

Fentanyl is a powerful opioid analgesic (100 times more potent than morphine) prescribe to people with moderate to severe pain. With a rapid onset lasting less than two hours, fentanyl is easily abused by people with chronic pain due to cancer or other serious diseases. Because it acts on the same brain receptors targeted by heroin and morphine, anyone using fentanyl is at high risk for developing an addiction.

Fentanyl analogs like carfentanil have chemical structures similar to fentanyl but are more potent. Carfentanil is the most powerful of all fentanyl analogs; according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), carfentanil’s potency is estimated to be 10,000 times more than that of morphine.

Overdosing on fentanyl happens so frequently because many heroin users don’t realize how much stronger fentanyl is than heroin. In addition, fentanyl coming from China may be “cut” with other harmful drugs or unknown substances to increase profits. Addicts buying fentanyl off the street really can’t be sure what they’re injecting or snorting.

Global Legal Status of Fentanyl

Fentanyl is illegal to possess (without a doctor’s prescription) or sell in most of Europe and Canada. In the U.S., fentanyl is listed as a Schedule II controlled substance by the DEA. Schedule II substances have a “high potential for abuse” but can be prescribed by physicians for relieving pain. Other drugs classified as Schedule II drugs include Adderall, hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone.

Fentanyl is illegal to possess (without a doctor’s prescription) or sell in most of Europe and Canada. In the U.S., fentanyl is listed as a Schedule II controlled substance by the DEA. Schedule II substances have a “high potential for abuse” but can be prescribed by physicians for relieving pain. Other drugs classified as Schedule II drugs include Adderall, hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone.

In 2015, the Chinese government enacted laws banning over 100 synthetic drugs and chemicals, including a few fentanyl products. However, the problem with fentanyl production and sales continues because when one drug is banned, opportunistic Chinese drug makers create a new one to replace it.

In 2017, China banned the manufacturing and selling of four fentanyl analogs. Although U.S. DEA officials called this move a “game-changer”, the influx of fentanyl from China into the U.S. continues today unabated and seemingly unstoppable.

Today, it’s illegal to produce and sell fentanyl, carfentanil, valeryl fentanyl and furanyl fentanyl in China. But a Northeastern University professor of health and law sciences is not optimistic about China’s pledge to crack down on the drug.

Dr. Leo Beletsky says that Chinese enforcement of reducing fentanyl production and selling to the U.S. is “quite lax.” Dr. Beletsky also states that shutting down fentanyl supply routes has previously proved to be ineffective. “You’ve got to address what is causing the demand for fentanyl first,” he says. “People addicted to opioids or those with chronic pain who use opioids must have access to the right kind of care necessary to avoid heavy dependence on opioids.”

For one thing, he says, it’s not clear how much fentanyl in the U.S. actually comes from China, and through which means. For another, it’s not guaranteed that the latest China-U.S. agreement will actually do much to stop fentanyl from hitting U.S. streets.

Beletsky further states that even if China were to make a sincere effort at stopping the drug from being mailed to the U.S., other countries would simply move in and take China’s place as suppliers of fentanyl. In addition, it can be easily synthesized using cheap ingredients like piperidine, a compound used to make many pharmaceuticals. Compounds like these can be found for sale on the dark web or bought from unscrupulous chemists skilled at producing these ingredients.

If you need more information about fentanyl addiction or know someone who is addicted to opioids, call FHE Health today to speak to a staff member.