The “holiday blues'” are a fairly common occurrence whether you have a diagnosed mental illness or not. That doesn’t mean, however, that holiday depression is any less upsetting, especially if it’s you who’s feeling your depression is worse during holidays. Instead of holiday depression, however, what you may be experiencing is seasonal depression.

What Causes Seasonal Depression?

Seasonal depression is a mood disorder. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), seasonal depression is not a separate category. Instead, it is listed as major depressive disorder with a seasonal pattern. Formerly, the condition was referred to as seasonal affective disorder, or SAD. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) says that about five percent of U.S. adults have a depressive disorder (American Family Physician estimates 4-6 percent) and it lasts longer than just during the winter months, typically about 40 percent of the year. Winter blues or depression during holidays is a milder form of SAD, referred to as a subsyndromal type of SAD, or S-SAD. Some 10 to 20 percent may have mild SAD.

Seasonal depression is a mood disorder. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), seasonal depression is not a separate category. Instead, it is listed as major depressive disorder with a seasonal pattern. Formerly, the condition was referred to as seasonal affective disorder, or SAD. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) says that about five percent of U.S. adults have a depressive disorder (American Family Physician estimates 4-6 percent) and it lasts longer than just during the winter months, typically about 40 percent of the year. Winter blues or depression during holidays is a milder form of SAD, referred to as a subsyndromal type of SAD, or S-SAD. Some 10 to 20 percent may have mild SAD.

As for the causes of holiday depression, the answers are unclear. However, experts believe its onset is triggered primarily by a biochemical imbalance in the hypothalamus area of the brain and is brought on by shorter daylight hours. This causes a change in the body’s circadian rhythm and results in the individual feeling out of sync with their normal routine.

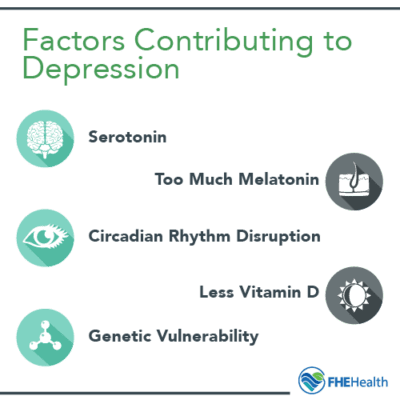

The following factors may contribute to seasonal depression:

- Serotonin regulation difficulty – Serotonin is a neurotransmitter thought to be responsible for balancing mood and affecting sleep and appetite. In winter months, some individuals suffering seasonal depression had 5 percent more of a protein called SERT, which is a protein that helps transport serotonin, than during the summer months. Higher levels of SERT translate to lower activity of serotonin, thus leading to depression. During the summer months, however, there’s more available sunlight, which tends to keep SERT levels lower.

- Too much melatonin production – The pineal gland in the human body produces melatonin, which is a hormone that reacts to darkness by causing the person to become sleepy. With dark winter days, the body produces more melatonin, resulting in those with seasonal depression becoming increasingly lethargic and sleepy. Medical experts caution that even though melatonin probably has a role in causing seasonal depression, it’s not the sole cause.

- Circadian rhythm disruption – The one-two punch of lowered serotonin activity and increased melatonin production affects the body’s circadian rhythm. Think of circadian rhythm as the body’s internal clock, synchronizing itself to daily light-dark changes and those occurring throughout the year. Important timing tied to sunlight is when to get up in the morning, for example. Those who suffer with seasonal depression, however, have different timing in their circadian signal, which makes bodily rhythm adjustment difficult.

- Less production of Vitamin D – Individuals with seasonal depression may not be able to produce sufficient Vitamin D, as the days get shorter and darkness is long and their skin is less exposed to sunlight. Vitamin D appears to play a role in the activity of serotonin in the body. Research shows some associations between Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency and depressive symptoms that are clinically significant.

- Genetic vulnerability. There’s some evidence that genes play a role in the development of seasonal depression. The condition, which does tend to run in families, may make some family members vulnerable to SAD.

Symptoms of Holiday Depression/Does it Differ from Clinical Depression?

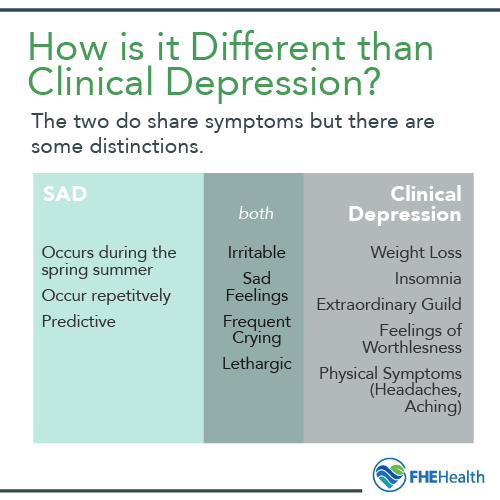

Depression during holidays has specific symptoms that are atypical from symptoms of clinical depression, while the two also share symptoms. With holiday depression, you often crave carbohydrates and sugars, tend to isolate yourself from others, sleep a lot more than normal and experience an increase in appetite. You’re also more irritable, feel sad, even cry frequently. With an accompanying lack of energy, feeling lethargic and tired, you’ll often find yourself cutting back on activities. It’s also difficult to concentrate when you’re going through depression around the holidays.

Depression during holidays has specific symptoms that are atypical from symptoms of clinical depression, while the two also share symptoms. With holiday depression, you often crave carbohydrates and sugars, tend to isolate yourself from others, sleep a lot more than normal and experience an increase in appetite. You’re also more irritable, feel sad, even cry frequently. With an accompanying lack of energy, feeling lethargic and tired, you’ll often find yourself cutting back on activities. It’s also difficult to concentrate when you’re going through depression around the holidays.

SAD that occurs during the spring and summer, on the other hand, is generally characterized by symptoms more typical of depressive disorder, including reduced appetite and sleeplessness.

With clinical depression, weight loss, insomnia, extraordinary guilt, feelings of worthlessness, and physical symptoms such as headaches and body aches that have no apparent specific cause, can occur. Clinically diagnosed depressed individuals also are less able to engage in activities they once found enjoyable, although this is a symptom also shared by those who have seasonal depression.

Some individuals who have SAD can experience symptoms that are as severe and debilitating as those with diagnosed clinical depression. In both SAD and clinical depression, suicidal thoughts may be present. For this reason, suicide assessments should be conducted for anyone a medical or mental health professional suspects may currently have or previously had SAD.

Another notable difference between seasonal depression and clinical depression is that the former tends to occur repetitively and be most severe seasonally, in the months of December, January and February, but better the rest of the year (while the latter can persist year-round).

Since seasonal depression is predictive, preventative treatment approaches, such as light therapy, psychotherapy, antidepressants and changes in lifestyle, can be implemented to make day-to-day activities less uncomfortable and disruptive for those who have the condition.

What Puts You at Risk for this?

A study published in Depression Research and Treatment found that women are four times more likely to have seasonal affective disorder than men. Furthermore, the age at SAD onset is typically estimated at between 18 and 30 years. With women and SAD prevalence so noteworthy, shift workers, such as nurses, who have less sunlight exposure, may be more at risk of developing the disorder.

WebMD lists a few other risk factors for seasonal affective disorder, including having a family history of depression or SAD, living far from the equator, and having either major depression or some other depressive disorder, such as bipolar disorder.

How this Occurrence can Affect Particular Communities More

Research in 2007 found that seasonal affective disorder and major depressive disorder are common among college students, while seasonal affective disorder is the more prevalent. In the groups studied, among male students, 85 percent had no depression, while there were 11 percent that qualified for seasonal affective disorder and four percent for major depressive disorder. Among the female students, the percentages were: 49% with no depression, 42% qualifying for seasonal affective disorder, and 9% for major depressive disorder.

Several studies found that the prevalence of SAD is greater in those living in higher northern latitudes, its prevalence varied across ethnic groups, and was also found in children and adolescents. Across 20 retrospective studies, prevalence estimates of SAD varied up to roughly 10 percent.

Prior Mental Health Diagnosis

Prior Mental Health Diagnosis

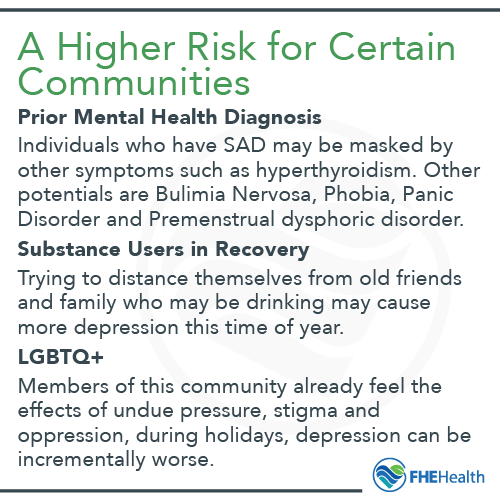

A mental health diagnosis is a guide for treatment; it doesn’t define a person. Often unreported and difficult to diagnose, SAD may be masked by other symptoms, such as hyperthyroidism. Indeed, those individuals who have SAD, even though they don’t know it, may have subtle thyroid function decreases.

Seasonal affective disorder can also occur along with eating disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse, making it even more difficult to pinpoint SAD. Other potential concomitant mental disorders include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), bulimia nervosa, phobias, panic disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Substance Users in Recovery

There’s no question that substance users in recovery feel the effects of depression around the holidays to a greater extent than during other times of the year. For one thing, they’re perhaps keenly aware of the mismatch between the expected joviality of the season and what they personally feel. While others are going to parties, and the holiday expectations tend to be magnified at this time of the year, those in recovery from substance abuse are doing their best just to stay sober. Trying to distance themselves from drinking family and friends may further increase their feelings of loneliness and depression, to the point where they resort to drinking as a coping mechanism and experience a SAD-triggered relapse.

LGBTQ+ Community

Members of the LGBTQ+ community already feel the effects of undue pressure, stigma and oppression for their lifestyle by intolerant people and those who lack understanding or compassion for what it means to be an LGBTQ+ individual. During the holidays, however, if self-identify as LGBTQ+, depression around the holidays can be incrementally worse.

Depression worse during holidays, unfortunately, is not atypical for LGBTQ+ community members, many of whom have suffered a significant disconnection and loss of family relationships due to being ostracized and not accepted. Alone, unable to share close bonds with the nuclear family takes a toll, making anyone who also has seasonal depression feel even more isolated than before.

Knowing that seasonal and holiday depression are generally time-limited and predictable means that you can get help to reduce the unpleasant and perhaps debilitating symptoms. Contact FHE Health to jump start a treatment program that can get you back to enjoying your life again.