She first knew something was wrong in February 2021.

“One day, out of nowhere, my right hand suddenly felt paralyzed,” recalled 18-year-old Catalina Artuz, in an interview with FHE Health. She couldn’t “scroll through her phone, open a door, or even hold a fork properly at lunch.”

“It was as if there was a complete disconnect between my brain and my hand — something I had never experienced before.”

Until then, Catalina was a happy, healthy kid who assumed her life would follow a “linear” path: “You have hobbies; you make friends; you go to school, then college; and everything follows a predictable sequence.”

Life as a Kid Before the Traumatic Diagnosis

Growing up, Catalina loved the outdoors and playing outside with her many friends. The warm climate of her hometown Cali, Colombia’s third largest city, made it easy to spend “entire days” playing outside with friends “under the sun.”

Growing up, Catalina loved the outdoors and playing outside with her many friends. The warm climate of her hometown Cali, Colombia’s third largest city, made it easy to spend “entire days” playing outside with friends “under the sun.”

In addition to an active social life, Catalina had many interests. She was “very artsy” and “could spend hours painting, building things out of cardboard, or turning random objects into little inventions.” She played the drums, guitar, and piano, and ultimately gravitated more to the piano. She also excelled in the classroom and on the tennis court.

In all these pursuits, Catalina’s right hand “served as my closest companion and collaborator in all my adventures and creations,” she said. “It catapulted me into excellence in every hobby I tried. I never thought about how much I relied on it until I lost its function.”

Catalina harbored similar presumptions about her health:

There’s a saying: “Good health is a crown worn by the healthy, but only the sick can see it.” That perfectly describes what I realized — I had never truly appreciated what it meant to be healthy until I lost it.

Other aspects of life were also easy to take for granted:

I was a brilliant student, but I wasn’t particularly disciplined. I also had many friends, but I didn’t fully appreciate the time I had to spend with them. I wasn’t religious either, because I never thought much about what life would be like if any of those things — my family, my friends, my education, or my health — were ever taken away from me.

Paralysis, Seizures, and Depression

Over time, that initial sensation in Catalina’s right hand spread to the rest of her right arm, then on from there, until “my whole upper right side felt completely detached from my brain,” she said.

She went to multiple doctors and underwent “every possible medical test” except an MRI. Then came the first seizure.

In the months that followed, Catalina’s condition deteriorated rapidly. She had always associated good health with happiness, “so when my illness took away my ability to do the things I loved, I fell into a deep depression,” she said.

Catalina’s symptoms continued to escalate in severity, but it would still be another few months before she’d be diagnosed.

The Diagnosis and Emergency Brain Surgery

One day she had to be rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. That is when she learned that she had a cancerous brain tumor that required emergency surgery. The doctors informed her mother “that the tumor was so large” that Catalina “would need to be taken to the ICU immediately and operated on within two days.”

By this time, Catalina was vomiting non-stop between seizures, couldn’t speak, and couldn’t think clearly. She didn’t even recognize her family or fully understand what was happening to her, and her vital signs were so low that she needed to be revived.

“So much time had passed that the tumor had likely progressed from stage 1 to stage 4, which is terminal,” she said.

The Long Haul of Recovery and Its Many Lessons

After a nine-hour craniotomy, “recovery started immediately.” Thankfully, even with the next hurdle ahead — the added trauma of chemotherapy and radiation — life “changed for the better.”

“In a way, it felt like a rebirth,” Catalina said. But she also “wasn’t the same person anymore” and had to “relearn everything,” from recognizing faces to walking, brushing teeth, eating with a spoon and fork, putting on a shirt, opening doors, writing, and tying her shoelaces.

At first, paralysis still affected her entire right side, from her shoulder to her fingertips, and the prospect of having to relearn the most basic of skills made Catalina “incredibly frustrated and sad.” With “time, therapy, and patience,” she began to regain control of her right hand. Gradually and painstakingly, over time, she began to regain the old sense of sensation in her right side, learning to count even “the tiniest twitch” in her fingers as progress.

Starting over was incredibly hard, but now Catalina “carried all the lessons … from fighting through those months of illness.” The biggest change was an appreciation for life and “the little things”:

I remember the joy I felt when my oncologist finally let me eat a cheeseburger again. Or how much it meant to see my friends waving at me through a glass window, because COVID was at its peak and they weren’t allowed to visit me in person. Even just feeling the grass beneath my feet or the breeze on my face became something I cherished.

“After facing the possibility of losing everything, I started seeing beauty in the smallest moments,” she said.

The Healing Power of Faith, Gratitude, and Resilience

Seemingly small victories became teaching moments and lessons in self-growth. Take, for example, when Catalina first managed to tie her shoes again. In that moment, “I understood that healing is not about returning to who I was before but embracing who I was becoming,” she wrote in her application essay.

Seemingly small victories became teaching moments and lessons in self-growth. Take, for example, when Catalina first managed to tie her shoes again. In that moment, “I understood that healing is not about returning to who I was before but embracing who I was becoming,” she wrote in her application essay.

In this process of self-transformation, Catalina discovered that “my relationship with God and my ability to be grateful — both of which were non-existent before — became the greatest gifts I could have ever received from such a difficult illness.”

Ultimately, Catalina was to find that, as she wrote in her essay, “recovery wasn’t just about regaining strength; it was about understanding resilience, patience, and the profound role that mental health plays in healing.”

College and Professional Aspirations

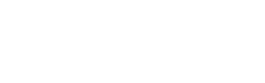

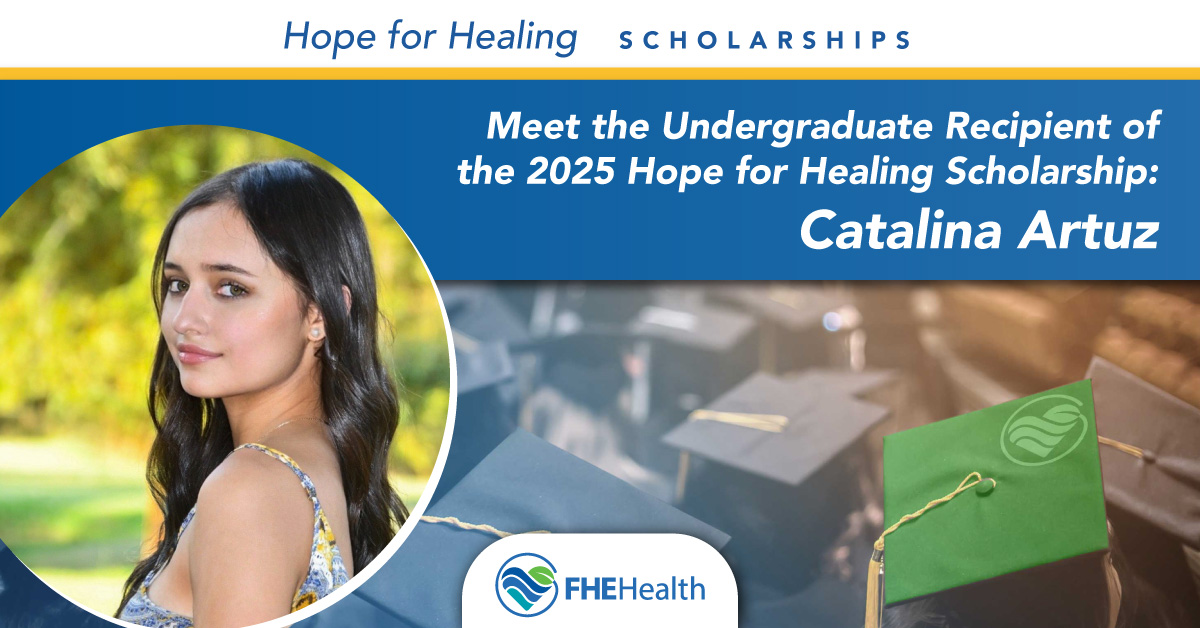

Today, Catalina is preparing to study psychology at Pepperdine University. Eventually, as a trauma-informed care psychologist working with those who face difficult medical challenges, she hopes to advocate for the integration of psychological care in hospital treatment plans. Far too often, the focus on physical symptoms means that mental and emotional conflicts go unaddressed, she observed in her essay.

Catalina is also on a mission: to continue her research in mental and emotional resilience, “exploring how therapy, faith, and community support can aid in recovery for patients facing medical trauma.”

Post-Traumatic Stress: Sources of Hope and Healing

Of course, healing from any trauma doesn’t happen overnight. It’s “not a straight-line process” and is “messy, aggravating, and occasionally heartbreaking,” Catalina wrote in her essay.

“The reality is, I still carry a lot of post-traumatic stress from what I went through,” she told FHE.

There still are “tough days, especially emotionally,” and physically, she continues to face challenges. She’s not yet able to individually move her right fingers; and she lives with various long-term effects of her diagnosis and treatment.

Still, Catalina exudes hope for healing. She cited phantom limb studies in “neuroplasticity,” the brain’s ability to heal and rewire itself, that demonstrate how the brain builds new connections after traumatic injuries. These findings are a “source of hope” that, with time and more hard work and patience, she’ll continue to recover.

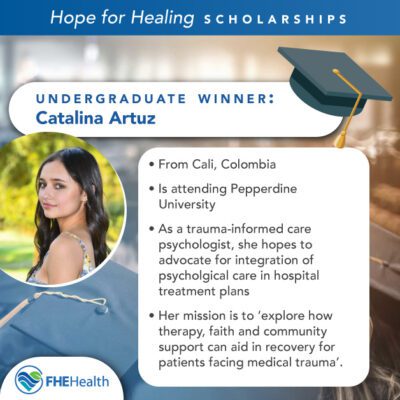

Catalina also draws great hope and strength from her faith in God and the love and support of family and friends: “On my worst days, when I felt like giving up, I reminded myself that I wasn’t’ fighting alone. Faith, family, and friends — they all carried me forward.”

Parting Words of Encouragement

What parting words of encouragement would Catalina give others living with a serious disease or diagnosis?

“You are not defined by your setbacks — you are defined by how you overcome them. That is when you prove, not only to yourself but to everyone around you, that you are truly a strong person.”

For more inspiration, catch the story of this year’s graduate recipient of the Hope for Healing Scholarship on March 24.