It’s been well-documented that the way addicts are treated in prison does practically nothing to support recovery, and recent news is showing that in some areas, this trend is worsening despite legislation intended to counteract these issues. In a Boston-area jail, an inmate was refused his right to take prescribed methadone for an opioid addiction. In Vermont, research suggests that less than 10 percent of medical requests for addiction treatment are granted in state prisons.

These cases fly in the face of rulings that have stated that penal institutions must provide essential medical services to the inmates they house.

In this article, we’ll discuss how these are just a few examples of how society is strained when addiction is “handled” in the criminal justice system, rather than in dedicated addiction treatment institutions.

Why Addicts Go to Prison

In the past few decades, society has come a long way in regard to our collective views on addiction. We’ve discovered that addiction is a disease that resembles chronic conditions like diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure in its basic characteristics.

In the past few decades, society has come a long way in regard to our collective views on addiction. We’ve discovered that addiction is a disease that resembles chronic conditions like diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure in its basic characteristics.

Somehow, though, as much as we try to build understanding about addiction and how to help patients overcome the acute symptoms of this long-term disease, the criminal justice system continues to treat addiction as a crime.

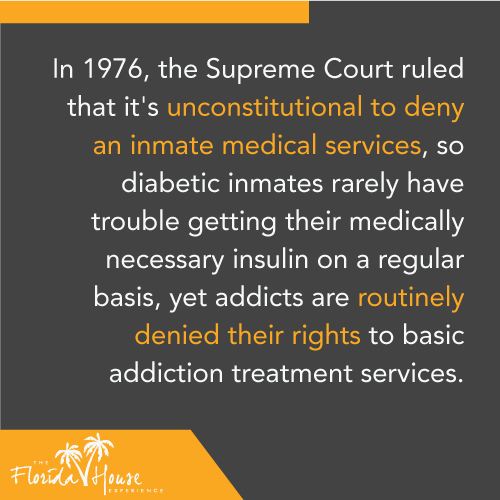

In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled that it’s unconstitutional to deny an inmate medical services, so diabetic inmates rarely have trouble getting their medically necessary insulin on a regular basis, yet addicts are routinely denied their rights to basic addiction treatment services.

This stems from the belief that addiction is a moral defect, which was exacerbated further with the U.S. War on Drugs in the 80s and 90s, mandatory minimum sentencing requirements for possession and other legal statutes that have led to disproportionate penalties that drug users have faced over many other classes of criminal offenders.

How the Justice System Is Failing Addicted Inmates

Disregarding briefly the way the legal system hurts the victims of addiction, once they enter the criminal justice system, the positive programs are few and far between.

Disregarding briefly the way the legal system hurts the victims of addiction, once they enter the criminal justice system, the positive programs are few and far between.

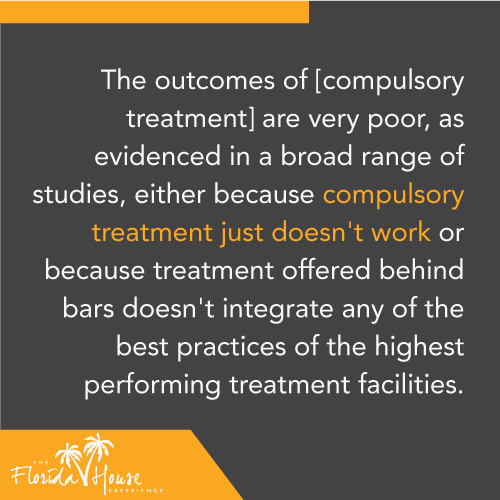

Many treatment programs behind bars are what are known as compulsory treatment programs, where inmates are forced to complete limited addiction treatment. The outcomes are very poor, as evidenced in a broad range of studies, either because compulsory treatment just doesn’t work or because treatment offered behind bars doesn’t integrate any of the best practices of the highest performing treatment facilities.

There are also inherent issues of jail and prison that ensure that incarcerated addicts get worse behind bars more often than they get better. Notoriously, drugs aren’t difficult to access in prison, and addicted inmates usually have plenty of opportunities to expand the severity of their disease or extend it to different substances.

There Are Silver Linings

Despite the damage being done to addicts as they serve sentences, occasionally something positive will happen. For example, President Obama notably released over 330 nonviolent drug offenders before he left office.

The existence and increased funding of drug courts is a positive development as well. These are specially designed areas of the justice system where inmates are seen as addicts more than they’re seen as drug offenders and treated as such. In cities where drug courts are being used more heavily, outcomes have involved a decrease in recidivism — which in this context suggests better recovery rates — and decreased financial burden on the criminal justice system.

What Lessons Can We Take Away?

It’s clear that denying an inmates right to medical treatment violates the Constitution, regardless of what’s occurring in the status quo. To enact sustainable change and a long-term benefit to inmates suffering from addiction, it has to be approached from a policy standpoint. Laws have to be written that help to change the narrative about so-called “drug crimes” and the people who get caught up in the system.

For more information, contact FHE Health today.